내일의 전통, 오늘의 관객을 만나다

월간국립극장

-

내일의 전통 SPOTLIGHT 더보기

-

무대, 탐미 STAGES 더보기

- 미리보기, 하나 -2023-2024 국립극장 레퍼토리시즌을 열며 공연의 감동, 일상의 힐링

- 미리보기, 둘 - 2023-2024 국립극장 레퍼토리시즌│국립창극단 시즌 프리뷰 최고의 솔리스트 앙상블

- 미리보기, 셋 - 2023-2024 국립극장 레퍼토리시즌│국립무용단 시즌 프리뷰 가치에 깊이 더하는 한국춤

- 미리보기, 넷 - 2023-2024 국립극장 레퍼토리시즌│국립국악관현악단 시즌 프리뷰 시도를 거듭하겠다는 출사표

- 미리보기, 다섯 - 2023-2024 국립극장 레퍼토리시즌│기획공연 시즌 프리뷰 풍성하고 다채롭게

- 미리보기, 여섯 - 2023-2024 레퍼토리시즌 공연 소개 60가지 기다림

- 미리보기, 일곱 - 2023-2024 극장 활성화 사업 일상에 활기를 더하다

- 미리보기, 이벤트 - 2023-2024 국립극장 레퍼토리시즌 능력 고사 이거 알면 공연 인싸

- 미리보기, 여덟 - 2023-2024 국립극장 레퍼토리시즌 프로그램 23-24 레퍼토리시즌 일정표

- 미리보기, 아홉 -국립국악관현악단 관현악시리즈Ⅰ<디스커버리> 첫 만남의 설렘

- 미리보기, 열 - 국립무용단 <온춤> 전통춤, 새 페이지를 열다

- 다시보기, 하나 -국립극장 기획공연 <우리 읍내> 평범한 이야기, 큰 울림

- 다시보기, 둘 - 국립국악관현악단 <부재> 예술하는 기술의 현재와 미래

-

안목의 성장 INSIGHT 더보기

-

극장 속으로 INTO THEATER 더보기

안동 하회별신굿탈놀이 공연을 처음 보았을 때 나는 완전히 넋을 잃었다. 물론 공연 전에 아내와 도수 40%의 안동 소주를 마신 탓도 있을 것이다. 공연은 활짝 웃는 모습의 탈을 쓴 백정이 소(물론 소의 복장을 한 배우들)의 머리를 두드리며 불알을 자르는 장면으로 시작한다.

그러고서 백정은 불알이 필요한 사람이 있는지 남성 관객에게 물어본다. “불알 사실 분 계십니까? 혹시 잃어버리신 분 계시오? 여기 신선한 고환이 있습니다!” 내 앞에서 펼쳐지는 이 심오하고도 풍자적 장면을 술에 취한 채 바라보고 있으니, 문득 미국 중서부 소도시의 정육점 주인이자 하회별신굿탈놀이의 백정과 똑같은 웃음을 지니고 계셨던 나의 할아버지가 떠올랐다.

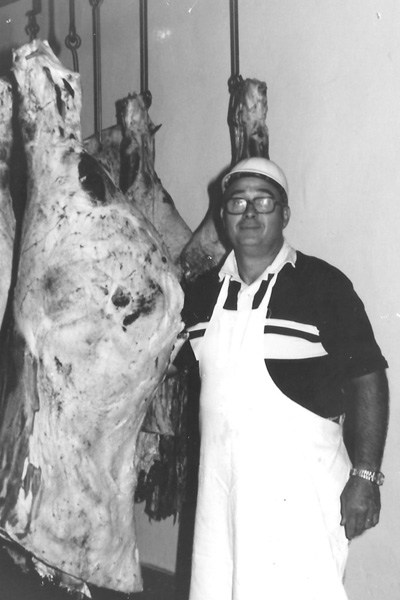

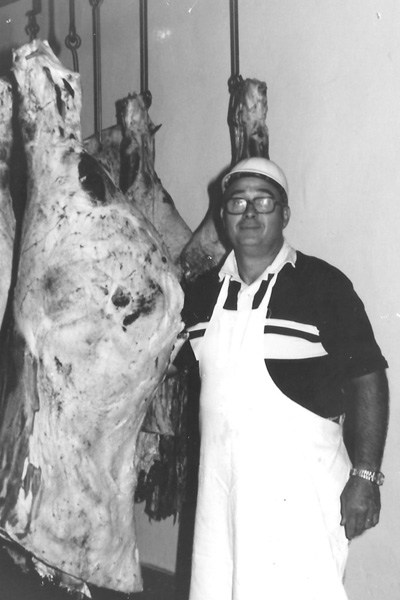

내가 초등학생이었을 때, 할아버지는 우리 가족이 운영하는 작은 동네 정육점인 번로커Berne Locker로 우리 반 아이들을 초대하셨다. 나는 어린 시절 대부분을 정육점에서 우리 가족이 마을 사람들에게 고기 판매하는 것을 보며 자랐다. 하지만 우리 반 친구들을 정육점에 초대하기 전까지 이곳에서 자란다는 게 얼마나 독특하고 특별한 것인지 전혀 몰랐다.

할아버지와 작은할아버지께서 천장에 매달려 있는 큰 소 사체를 가리키며 유쾌하게 각 부위를 설명하는 동안, 나는 그걸 처음으로 보는 동급생들이 점점 불편해하는 것을 느꼈다. 할아버지는 항상 미소를 머금고 친절하신 분이었지만, 때로 경계를 허무는 것도 좋아하셨다. 할아버지께서 신선한 소피가 가득 담긴 컵을 들고 안쪽 방에서 나왔을 때, 나는 몇몇 친구가 거북해하며 꿈틀대기 시작하는 것을 보았다. 할아버지께서는 어린 학생들에게 그 피를 가져다가 마실 사람이 있는지 물어보셨다.

안동에서 소주를 마시고 탈춤을 관람하던 중 피가 담긴 잔을 돌리며 활짝 웃는 할아버지의 모습이 떠오르며 머리가 복잡해졌다. 이 탈에 할아버지의 미소가 영원히 남아 있는 것 같았다. 탈에 새겨진 주름은 수십 년 동안 웃으며 사신 할아버지의 피부에 새겨진 주름과 닮았다. 배우가 관중을 올려다볼 때 탈의 턱에 달린 작은 끈으로 인해 더 큰 미소가 지어졌는데, 나는 문득 할아버지도 턱에 당신의 장난스러운 미소를 더 환하게 만드는, 보이지 않는 끈이 있었는지 궁금해졌다. 반 친구들은 겁에 질려 할아버지를 외면했다.

나이가 들어감에 따라 음식이 내 삶과 정체성에 깊은 영향을 준다는 사실을 깨닫게 되었다. 그러나 정육점과 같은 단순한 것이 한 개인, 가족, 도시, 심지어 국가에 얼마나 중요한지 이해하는 다른 아이들, 나아가 성인을 만나는 경우는 매우 드물다. 물론 여기저기서 나와 같은 사람을 찾았다. 뉴욕에서 석사 과정을 공부하는 동안, 나는 나와 같은 사람들과 친해지려고 고기와 치즈를 판매하는 장인의 가게에서 아르바이트를 했다. 내가 평생의 반려자인 커트니Courtney와 결혼한 이유 중 하나는 음식에 대한 그녀의 열린 마음과 예리한 입맛에 있다. 하지만 비로소 한국에 와서야 진정으로 내 자리를 찾았다.

한국으로 이사하는 것은 힘들었지만, 어떤 면에서는 내 고향보다 한국 문화가 더 편안하다는 것을 서서히 깨달았다. 내가 한국 문화를 편하게 생각한다는 것을 가장 확실하게 깨달은 순간이 있는데, 문을 열고 들어서자마자 오픈된 정육점 카운터가 있는 고깃집을 방문했을 때였다. 나는 환하게 웃는 할아버지의 얼굴을 떠올리며, 이 고기 천국에 대해 어떻게 생각하고 말씀하셨을지 상상했다.

내가 지금 살고 있는 곳인 대전 바로 외곽에는 유명한 고깃집이 있는데, 그 식당에 들어서면 가장 먼저 냉동 상태가 아닌 농가에서 키운 신선하고 거대한 옥천 흑돼지가 눈에 들어온다. 식당 주인은 손님이 고기를 직접 눈으로 볼 수 있도록 들어오는 모든 손님에게 신선한 삼겹살을 썰어준다. 하지만 이 고깃집 주인은 우리 할아버지처럼 웃지 않는다. 그는 끈을 잃어버린 것일까?

이런 식당을 방문하면, 나는 바로 삼촌과 할아버지가 고기를 썰고 뼈를 바르는 것이 일상이던 내 집에 돌아온 것 같은 기분이 든다. 하지만 우리는 항상 고객의 눈에 띄지 않는 안쪽 방에서 작업했다. 내 고향인 인디애나의 문화와 비교해 한국은 음식의 원산지에 대해 더 개방적인 것 같다. 실제로 고기의 품종과 식재료의 원산지를 맛과 품질을 좌우하는 중요한 요소로 여긴다. 내 고향에 있는 사람들 대부분은 바로 앞에서 저녁 식사 재료를 잘라주거나, 수조에서 꺼낸 신선한 활어를 죽여 내장을 제거하는 것을 보면 바로 몸부림을 칠 텐데, 한국에서는 이러한 관행을 권장하며 품질과 신뢰의 표시로 생각한다.

내가 유튜브 채널 ‘오스틴! 주는 대로 먹는다(Eating What is Given)’를 시작한 주된 이유도 바로 한국의 이러한 특징에 있다. 이 멋진 문화를 가족들과 공유하고 싶었다. 비록 보여드리기 전에 할아버지께서 돌아가셨지만, 왠지 모르게 고깃집에 가서 구이용 고기를 썰고 있는 정육점 주인을 볼 때마다 할아버지의 기운이 느껴지고 웃음소리가 들리는 것만 같다.

하회별신굿탈놀이에서 백정은 관객에게 고환을 건넨 뒤 소의 심장을 도려낸다. 다시 그는 관객 사이를 돌아다니며 심장을 판다. “여기 심장 잃어버리신 분 계십니까? 분명 심장을 잃어버리고 필요하신 분이 많을 텐데요! 이 심장을 사서 넣으세요!” 이유는 모르겠지만 세상 무엇보다 그 심장이 필요하다고 외치고 싶었다. 하지만 외치지 않았다. 반 친구들이 방문했을 때에도, 할아버지가 나에게 피가 담긴 잔을 주셨을 때 나는 그것을 받아 마시고 싶었다. 하지만 마시지 않았다.

할아버지는 크게 웃으며 신선한 소피가 담긴 컵을 들고 한 번에 꿀꺽 마셨고, 붉게 물든 이빨이 드러나게 미소를 지으셨다. 이 모습에 친구들은 충격을 받고 난리가 났다. 마치 하회탈의 턱에 있는 끈이 당겨지듯 할아버지는 더 환하게 미소 지으셨다.

The first time I saw the Andong Hahoe Mask Dance performance, I was mesmerized. Of course, the bottle of 40%ABV Andong soju my wife and I shared before the performance certainly helped. The performance opens with a butcher wearing a wide smiling wooden mask knocking a beef cattle (actors in a cow costume, of course) in the head and cutting off its balls.

The butcher then walks around asking men in the crowd if anyone needs any balls. “Does anyone need to buy some testicles? Maybe yours are missing? I have some fresh testicles right here!” As I drunkenly stared at this deeply poetic and ironically humorous scene unfolding before me, I immediately thought of my grandfather, a butcher in my small midwestern town of America, who smiled exactly like this butcher in the Hahoe Mask Dance.

When I was in elementary school, my grandfather invited my class on a school trip to the Berne Locker, my family’s small local butcher shop. Growing up, I spent most of my afternoons and weekends here, watching my family serve meat to the people of the town. However, I had no idea just how unique and special growing up around this place truly was until my class was invited to experience it for themselves.

As my grandfather and his brother happily explained where meat and steaks come from, pointing to the large cattle carcasses hanging from the ceilings, I could feel discomfort growing in my inexperienced classmates. While my grandfather was always kind and smiling, he also loved to push boundaries now and then. And when he came out of the back room with a cup full of fresh cow blood, I noticed a few classmates start to squirm with discomfort. He began to offer it to my young classmates, asking if anyone wanted to take some of the blood and drink it.

My grandfather’s big wide grin while passing around the cup of blood is what shot through my soju addled brain while watching the mask dance in Andong. It felt like my grandfather’s very own smile was immortalized in this wooden mask. The wrinkles carved into the face mimicked my grandfather’s own wrinkles carved into his skin from decades of smiling. A small string attached to the mask’s jaw would widen the mask’s smile as the actor looked up at the crowd, and I suddenly wondered if my grandfather also had some invisible string in his jaw that widened his mischievous smile, way back then, when all my classmates turned away with fright.

As I got older, I came to realize that food was a profound part of my life and identity. However, it was rare to find other children, and later adults, who understood just how important something as simple as a butcher can be for individuals, families, cities, and even countries. Of course, I found others like me here and there. While studying for my master’s degree in New York, I took a part time job at an artisanal meat and cheese shop, just to be close to others like me. I married my lifelong partner, Courtney, partly because of her open mind and sharp palate when it comes to food. But it wasn’t until I moved to Korea that I truly found my place.

While moving to Korea was challenging, I slowly started to realize that, in some ways, I felt more at home within this culture than my own back home. My most tangible memory of realizing I had a place in this culture was when visiting a gogi-jip (meat house, 고기집) that had an open butcher counter as you walked in the door. I pictured my grandfather's smiling face, imagining what he might have thought or said about this meat wonderland.

Just outside of Daejeon, my home in Korea, there is a popular gogi-jip where a huge side of unfrozen and fresh farm-raised Okcheon black pig is the first sight you see when you walk in the door. The owner of the restaurant slices pork belly fresh to order for all the patrons entering to witness with their own eyes. The owner here never smiles like my grandfather did though. I wonder if he lost his strings?

When I visit restaurants like this, I immediately feel like I am right back at home, watching my uncles and grandfather slice up meat and break down carcasses. But we always did the processing in the back room, away from the prying eyes of customers. Compared to my home culture in Indiana, I feel that Korea is more open about where their food comes from. In fact, breeds of animals and origins of ingredients are seen as important to the taste and quality of the meat. While many of the people in my hometown would immediately squirm at the thought of seeing pieces of their dinner being cut up before them or a live fish being killed and gutted fresh from the tank, in Korea, this practice is encouraged and a sign of quality and trust.

This aspect of Korea is a major reason why I started my YouTube channel, Eating What is Given, so I could share this amazing culture with my family. Even though my grandfather passed away before I had the chance to share it with him, for some reason, I feel his spirit and can hear his laugh every time I visit the gogi-jip and watch butchers slicing up meat for the grill.

In the Hahoe Mask Dance, after the butcher offers the crowd the testicles, he then cuts out the heart of the cattle. Again, he walks around the crowd, offering a heart to all the patrons. “Who here has lost their heart? Surely, many of you need a heart because you’ve lost yours! Buy this one and put it in!” I’m not sure why, but I wanted to cry out that I needed that heart more than anything else in the world. But I didn’t. Just like during my class field trip, when my grandfather offered the cup of blood to me, I wanted to take it and drink it down. But I didn’t.

With a big laugh, my grandfather took the cup of fresh cow blood and drank it down in one gulp, smiling with big, red-stained teeth as my classmates went hysterical with shock. His smile widened, like the strings being pulled on the jaw of a wooden mask.

Translator. Moony Choi

월간지 '월간 국립극장' 뉴스레터 구독 신청

뉴스레터 구독은 홈페이지 회원 가입 시 신청 가능하며, 다양한 국립극장 소식을 함께 받아보실 수 있습니다.

또는 카카오톡 채널을 통해 편리하게 '월간 국립극장' 뉴스레터를 받아보세요.

※회원가입 시 이메일 수신 동의 필요 (기존회원인 경우 회원정보수정 > 고객서비스 > 메일링 수신 동의 선택)